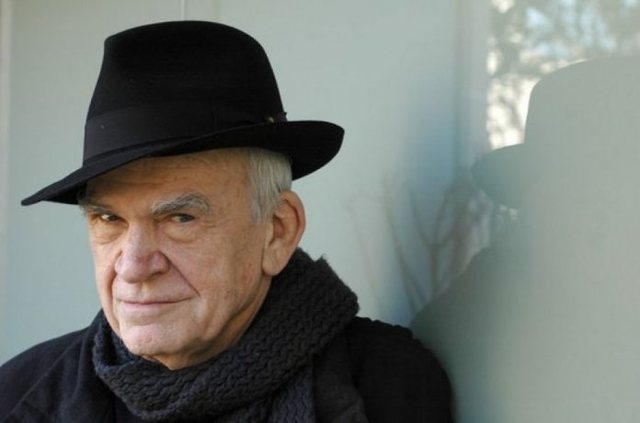

What Milan Kundera thought about Mozart, Bach and Beethoven

The Call of the Past by Milan Kundera

During a radio conference in 1931, Schönberg speaks of his teachers: “in erster Linie Bach und Mozart; in zweiter Beethoven, Wagner, Brahms”, “in first place Beethoven, Wagner, Brahms”. Then, in condensed, aphoristic stages, he defines what he learned from the five composers.

Meanwhile, between the reference to Bach and others, there is a very big difference: in Mozart, for example, he appreciates “the art of phrases of common lengths”, or “the art created from secondary ideas”, therefore a completely personal ability, which belongs only to Mozart. In Bach he discovers those principles, which had been for all music during the centuries before Bach: primo, “the art of inventing groups of such notes that can be accompanied by themselves” and, secundo, “the art of creating everything, starting from a single node, “die Kunst, alles aus einem zu erzeugen”.

Through two phrases, which summarize the lesson that Schönberg learned from Bach (and his successors), every dodecaphonic revolution can be defined: completely different from classical and romantic music, which are composed on the alternation of different musical themes that follow each other, a Bach fugue, like every dodecaphonic composition, from beginning to end, is developed starting from a single node, which is melody and accompaniment at the same time.

Twenty-three years later, when Roland Manuel asked Stravinsky: “What are your great devotions today?”, he replied: “Guillame de Machaut, Heinrich Isaak, Dufy, Perotin and Webern.” It is the first time that a composer openly declares the great importance of the music of the 12th, 14th and 15th centuries and cries out to modern music (of Webern).

A few years later, Glenn Gould gave a concert for the students of the conservatory in Moscow; after playing Webern, Schoenberg and Krenek, he addressed the audience for a brief comment and said: “The most beautiful praise I can give for this music is to say that the principles that can be found in it are not new, that they have existed for at least five hundred years”; he then continued with three fugues by Bach. It was a well-intentioned provocation: socialist realism, the official doctrine at the time in Russia, fought modernization in the name of traditional music; Glenn Gould sought to show that the roots of modern music (banned in communist Russia) go much deeper than those of the official music of socialist realism (which, in reality, was nothing more than an artificial preserve of musical romanticism).

* Excerpted from "Betrayed Testaments", Milan Kundera, Point Without Surface, Tirana 2011

Prepared by: ObserverKult

Happening now...

83 mandates are not immunity for Rama's friends

ideas

top

Alfa recipes

TRENDING

services

- POLICE129

- STREET POLICE126

- AMBULANCE112

- FIREFIGHTER128